Published on: December 2016

Manifestations of populism have been increasing significantly during the past few years. This behaviour started with people rising against ruling authorities in many emerging economy countries (for example during the Arab Spring). This movement spread to industrialized economy countries where many governments, in power or outgoing, lag or have been beaten by parties or movements opposing the existing order. The tone has been initially set in 2016 by the surprising decision of the British electorate to part ways with the European Union at the start of the summer followed by the election of Donald Trump as president of the United States in November and by the rejection of constitutional reforms by Italian voters in a December referendum. Note however that in December, the second take of the Austrian presidential election confirmed the results of the spring election of a pro-European candidate. This last vote should not be seen as invalidating the trend favorable to populism since for now, surveys for 2017 elections (in France, Germany and the Netherlands) are showing a rise in support for populist political parties.

The trend toward populism is being fed in particular by globalization and the perception of its negative impact on employment. Think only of the angry white male analogy used to summarily describe the typical Trump voter, whose education attainment is low and is a victim of the offshoring of low-skilled jobs.

Insightful research: the key to our expertise

It now seems that the benefits of globalization on the rise in living standards since the end of World War II(see following chart) are no longer enough to meet citizens’ expectations in the current context of slower trend economic growth. This backdrop creates fertile ground for candidates that put forward populist ideas.

GDP per Capita

A Brief Look at Populism

Populism does not sit to the right, the center or the left of the political spectrum but is rather defined as “…an ideology that pits a virtuous and homogeneous people against a set of elites and dangerous ‘others’ who are together depicted as depriving (or attempting to deprive) the sovereign people of their rights, values, prosperity, identity, and voice”.1 By accepting this definition, one can understand that political rhetoric that targets globalization as the main culprit for citizens’ plight can appeal to that part of the electorate feeling victimized.

Hence, in reaction to the symptoms afflicting these voters, populist political programmes will often include protectionist measures that hamper not only the free flow of goods and services but also of people, labour. In summary, these programmes lead to a decline in global economic integration, indeed, to national economies isolating themselves.

Probable Causes for the Rise of Populism

Yet, the increase in standards of living that we show in the first chart stems from the efficiency gains that flow in part from the integration of the global economy, the significant productivity gains and from the strong demographic growth that followed the end of the Second World War. In addition to generally increasing standards of living, this significant growth also resulted in the narrowing of the gap in inequality between countries with developing economies and industrialized economies.2 (see chart on next page)

Per Capita GDP in Industrualized and Developing Countries

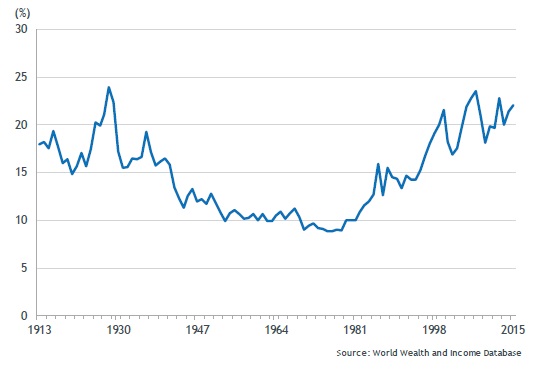

However, the distribution of these gains within each of these countries has generally been uneven, particularly during the last 30 years. For example, in the United States in 1980 the highest income percentile garnered 10% of all income including capital gains. In 2015, this highest percentile took up 22% of all incomes generated in the country3 (refer to the following chart). Another measure of income distribution, the Gini coefficient4, has risen from 37.7 in 1986 to 41.1 in 2013.5 China’s Gini coefficient also depicts a less equal income distribution, having risen from 29.1 in 1982 to 42.1 in 2009.6 The unequal distribution of the gains in living standards has disenfranchised a greater portion of the population, within both rich and poor countries, as the trend in growth has slowed.

Top 1% Income Share Including Capital Gains - United States

Consequences of Populist Economic Policies

One can hardly deny that the unequal distribution of the benefits from globalisation has contributed to increasing voters’ mistrust of their political leaders. Indeed, the displacement of economic activity between and within countries forces domestic economic adjustments whose impacts are not felt evenly. It would be surprising if the usual prescriptions of populist policies were the right answers to the challenges now confronting the global economy.

Nevertheless, from an economic standpoint, it is more efficient to allocate the production of goods and services according to each countries’ comparative advantages. Indeed, it is not by erecting trade barriers and by limiting immigration that sustainable economic growth will return. In fact, after a favourable initial impact, the inefficiencies fostered by such policies could lower living standards and once again widen the wealth-gap between rich and poor countries. Because of their impact on the size of businesses, operating on a smaller scale, these impediments to trade will result in higher prices. Gains in employment, initially following such protectionist measures, could well vanish with the drop in purchasing power resulting from higher prices.

The arrival of immigrants, who are often younger, alleviates the burden of an ageing population on public pensions and healthcare costs. Restricting the influx of new citizens could force governments to scale back some social programs.

The Long Journey to Solutions

We now seem to be at the stage where we need to think about how to keep the benefits from the strong growth of the previous decades in spite of the temptation to deviate from the path that led us there. Staying the course will not be easy since the efforts required to stay on track will only deliver results in many years.

To address the income and wealth distribution problems, economic policy should aim at achieving the delicate balance between wealth creation and its distribution. This is quite a challenge. Recently, governments have started to change course by pulling on the fiscal policy lever to support growth; however, the question about its distribution still remains unanswered. Fiscal competition between countries remains the most intractable hurdle to more progressive and distributive taxation.

Preserving free trade between states will probably prove an even greater challenge. It would indeed be a shame to prevent emerging economies from achieving their legitimate aspirations to a higher standard of living by raising trade barriers. Moreover, we will need to find ways to mitigate the impacts from international competition on citizens in industrialized economies. In these countries where real wages and the standard of living are already high, lasting gains will only flow from productivity. The solution necessarily requires policies aimed at enhancing the skills of the labour force to provide it with the useful tools to find a job. It is a key element in an economy that increasingly produces services requiring ever more technical and technological knowledge.

The challenges are considerable but we need to refrain from modifying too much the recipe that raised the standard of living of all citizens and reduced the number of people living below the poverty line.7 There remains however much more to be done in order to keep what we’ve achieved and to make sure it is well distributed.

1Daniele Albertazzi et Duncan McDonnell, Twenty-First Century Populism, http://www.palgrave.com/resources/samplechapters/9780230013490_sample.pdf), Palgrave MacMillan, 2008, p.3 tel que consulté le 7 décembre 2106 au https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Populisme_(politique).

2Mark Carney, The Spectre of Monetarism, Allocution prononcée par le gouverneur de la Banque d’Angleterre le 5 décembre 2016 à Liverpool, page 3. (http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/speeches/2016/speech946.pdf) Le gouverneur Carney y mentionne que le coefficient Gini pour l’économie mondiale a diminué de 0,74 en 1975 à 0,63 en 2010 reflétant une diminution de l’écart du revenu national moyen entre les pays.

3Données tirées du World Wealth and Income Database (http://www.wid.world/).

4Le coefficient de Gini mesure la distribution du revenu au sein d’une économie donnée. Sa valeur se situe entre 0, soit une distribution parfaitement égalitaire des revenus, et 1, une distribution parfaitement inégalitaire des revenus.

5Données tirées de la base de données de la Banque mondiale au : http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=US

6Données tirées de la base de données de la banque mondiale au :https://www.quandl.com/data/WORLDBANK/CHN_SI_POV_GINI-China-GINI-indexPoint

7Selon la Banque mondiale, le nombre de personnes vivant avec moins de $1,90 par jour est passé de 1,9 milliard à moins de 800 millions de 1981 à 2013. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=poverty-and-equity-database