After an extended period of sluggish economic growth, the global economy is showing increasing signs of progress. Some will say that the lethargy has lasted long enough and that it is high time for the long winter that followed the Great Recession to make way for more invigorating weather.

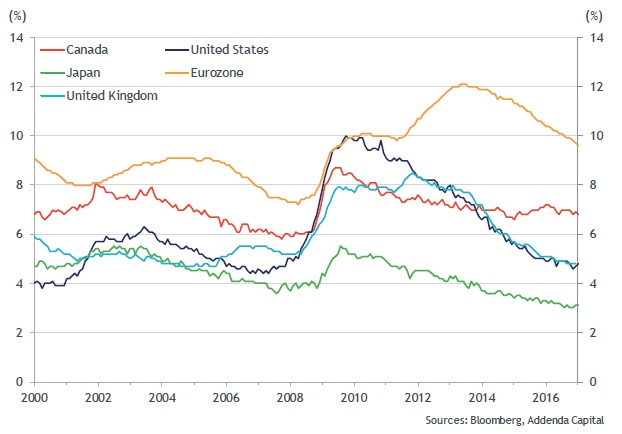

For some time now, low or declining unemployment rates in a number of countries have been hinting at warmer temperatures in the economic climate in North America, indeed, but also in Europe and in several other countries. And yet, heeding populism, governments seem to want to accelerate growth through expansionist spending and tax policies, even though economic growth has already started to pick up steam. It is also worth stressing that the economy’s cruising speed is probably lower today than it was a decade ago.

International Unemployment Rates

Insightful research: the key to our expertise

The decline in the economy’s potential growth rate is related in part to an ageing population and to slower growth in international trade and productivity gains. Unless public policies address these structural causes, the economic boost targeted by such policies will just push economic activity to its limits more quickly. We can then expect monetary policy – fearing a resurgence of inflation in the face of a disappearing output gap – to become less accommodative and to revert to neutrality or even to tightening.

Impacts of Tax Reform in the United States

Besides expansionist fiscal policies, the wave of populism is also opening the door to protectionist policies, especially in the United States. The tax reform planned by the new administration would include a border adjustment tax that may change the rules of the game for international trade and further fan the flames of domestic growth.

The proposed corporate tax reform, initiated by the Speaker of the US House of Representatives, Paul Ryan, and the Chairmain of the House Ways and Means Committee, Kevin Brady, and supported by the Trump administration, aims to replace the current 35% corporate income tax on global net income (which includes a large number of deductions and loopholes) with a flat 20% tax on net cash flows.

First, a reduction on this scale would make the taxation of corporations domiciled in the United States very competitive globally, whereas it is currently among the least favourable. In fact, it would eliminate the motivation for tax inversions1 that undermine the corporate tax base. Furthermore, the proposal would create a strong tax incentive to invest by allowing businesses to immediately deduct all of their capital expenditures, instead of gradually amortizing them as they do now.

One of the distinctive aspects of the proposed approach would be to add border adjustments based on the origin of the cash flows to the definition of the net cash flows subject to the 20% tax. In the formula put forward, proceeds from domestic sales (in the United States) would be subject to the tax, while revenues from exports would be exempted. This approach of exempting exports from the tax, is similar to the treatment of exports in countries that apply a value-added tax to domestic sales but exempt exports; Canada and several OECD countries refund the tax paid on exported goods and services.

The most controversial aspect, however, is the way imports would be handled. Under the proposal, all expenses for domestic inputs (i.e., labour and other inputs purchased in the United States) would be deducted from net cash flows, while the cost of imports would not be. This means that in terms of direct impact on after-tax profitability, using domestic inputs would cost 20% less than using imported goods and services costing the same in US dollar terms. All else remaining equal, this would generate a strong incentive for businesses domiciled in the United States to substitute local inputs for imported ones.

The potential impact of such border adjustments on growth in the United States and on international trade could be significant. It will depend on both the availability of labour and additional production capacity in the United States and on the exchange rate shift that the border tax adjustments may trigger.

Cases in Point

If the exchange rate remained the same, the profitability of US businesses with revenues sourced entirely from exports would be much improved: they would pay no more income tax, while currently their profits are taxed at 35%. These businesses would therefore be far more competitive in international markets and would definitely attempt to gain global market share. They could increase production if there were enough unused resources available in the United States, which is not clear at this stage of the cycle as evidenced by the already low unemployment rate and given the skills required.

Businesses that depend on imports for their inputs and that draw their revenue from the domestic market would become less profitable. Rather than paying a 35% tax on their profits under the current scheme, these companies would see all their revenues subject to a 20% tax because they would no longer be able to deduct the cost of imported goods and services. If they could replace these imports with domestic inputs (i.e., available in the United States), they would be highly motivated to do so, because they could then deduct these costs in computing net cash flows. Near term, if these substitute products or factors of production were not easily available in the domestic market, it is plausible that final prices would increase up until reaching the same profitability as before. Should this be the case, US consumers would bear the burden of the tax change, since they would have to pay a higher price for imported products.

The other polar case would see the exchange rate on the US dollar appreciating to completely offset the impact of the border adjustments2. In this case, the increased exchange rate would lower the revenues of US exporters by 20%, which could even reduce their net profitability despite the proposed change in the tax regime. For importers, the dollar’s stronger exchange rate would compensate for the fact that their imports could not be deducted from their net cash flows. In this instance, foreigners would have to bear the burden of the border tax adjustments, through increased terms of trade: foreign exporters would receive fewer dollars for their exports, and US exports would cost more for their foreign buyers.

Impacts of Public Policies on Economic Conditions

Governments are facing the challenge of renewing infrastructures, many of which are approaching the end of their useful life. Significant spending will be necessary to carry out the required repairs and upgrades. The jury is still out, however, on what should be the optimal amount of such investments at this stage of the business cycle. Indeed, if more synchronized global growth is happening, increased demand for labour in the construction industry may prove difficult to meet.

In Canada, the number of construction jobs barely declined during the Great Recession (-48,000) and has steadily increased ever since (+201,000). Today, the construction industry employs 6.2% of the workforce, an all-time high, although not an outlier by international standards. The situation is somewhat different South of the border, where, of a total of 8.7 milion jobs lost during the Great Recession, 2.2 million were in construction. Since the beginning of the recovery, jobs in this sector have only increased by 1.3 million, suggesting there might still be available workers. Today the sector represents 4.3% of the labour force. But as employment in this sector was depressed for 4+ years, we can assume that many unemployed construction workers have found work elsewhere. This is especially likely given today’s low overall unemployment rate of 4.7%. Accordingly, it would not be surprising if increased demand for labour in this industry triggered wage pressures and more inflation3.

As for any possible contribution to growth from a reform of taxation, it appears that an ambitious overhaul like the one contemplated in the United States could improve growth prospects in the medium and long terms. A tax system that encourages multinationals to remain in the United States and that fosters investment and entrepreneurship would increase the economy’s productive capacity. In the short term, measures that promote capital expenditures could ratchet current growth up a notch. Other tax relief for individuals could stimulate already robust consumption. Any tax cut would also further complicate the task of achieving a sustainable fiscal balance.

In Canada, the new federal government rose to power on a promise of major infrastructure spending and tax breaks for the middle class. The current federal budget plan calls for larger budget deficits with no end in sight, an unenviable situation at this stage of the cycle. Eventually the plan will have to be modified to restore a balanced budget, but that could be problematic if the current cycle ends before the government has regained some budgetary leeway.

Understanding the Nature of the Cycle

More synchronized global growth will soon require adjustments in monetary policy, which could precipitate the end of the current cycle. It can be helpful to differentiate between two types of cycles. Typically shorter, more dynamic cycles, in which inflation becomes a clear and imminent threat, compel central banks to aggressively tighten credit. During these cycles, significant interest rate hikes end up choking the elements of aggregate demand that are most sensitive to interest rates, such as residential investment, consumer spending on durables and business investment. The other kind of cycle, which is more drawn out and features more sluggish growth, ends differently. These longer cycles often lead to excesses that build up and create financial vulnerabilities. Monetary tightening is often much less intense, but the vulnerabilities magnify its impact. Sometimes it can even be a final surge of enthusiasm that bursts an already overinflated bubble.

The current cycle fits in this second category. Today’s vulnerabilities have been created by the financial repression that has existed since the Great Recession. By keeping interest rates down and making massive purchases of government bonds, central banks have pushed most bond yields below zero net of inflation and forced traditionally conservative investors into riskier investments. The inflated prices of several asset classes make them vulnerable to a strong correction in an improving growth environment where central banks may be compelled to reduce financial repression. The Federal Reserve has already embarked modestly on this route. With more synchronized growth, other central banks will have to follow suit, because they need to find some room to manoeuvre before the next recession. In this context of pro-cyclical budgetary policies, keeping the cost of credit down for too long could have serious consequences and give the economy more than a shiver.

1High current taxes encourage US companies to merge with partners in other countries where taxation is more taxpayer-friendly and to move the head office of the merged entity abroad.

2A 25% increase in the value of the US dollar would be required to eliminate the gain from exempting exports from the tax and to reduce the dollar price of non-deductible imports so they generate the same net after-tax profitability. For example, a $1.00 input from the United States, and therefore deductible, would cost $0.80 net after tax, while an imported (non-deductible) input that cost $1.00 before the change in the exchange rate would cost $0.80 if the exchange rate rose from $1.00 to $1.25 (1/1.25).

3It is possible that many workers, in the construction or in other industries, withdrew from the labour force in the years following the Great Recession as witnessed by the decline in the participation rate. Should these workers reintegrate the labour market, then wage pressures could be weaker.